The exploitation of Nepal migrant workers

Source: Amnesty International

Source: Amnesty International

During our research in Nepal, we found that a majority of youth in the villages did not stay at home, but was working as migrant workers in Kathmandu or elsewhere abroad. Generally speaking, migration is one of the more effective methods of coping with economic stresses. By sending an individual working elsewhere, the household diversifies the risk of losing their major income sources, such as agriculture. Additionally, if the migrant worker sends regular remittances back home, it increases the available capital within the household that can be used for further investments in education, agriculture or health. All of these positive impacts, however, are based on the assumption that the migration process happens without significant barriers.

Recently, Amnesty International published a report on the exploitation of Nepali migrant workers abroad. 88% of interview respondents said they had to pay agent fees to find jobs overseas. These fees are so high that migrants have to borrow over half from money lenders, which put migrants in debt. Once arrived at their overseas locations, these migrant workers receive lower pay than what was promised by the agents. Since the transactions between the agent and worker are informal or go through some middlemen, the migrant workers don’t have any legal stance against them. As a result, they are stuck in a cycle of debt that would take years of work to pay off.

When communities that are ravaged by water scarcity, landslides or earthquakes chose to send their family members away to work, this is often their last resort to increase the income for the family. For the case of Nepal, however, going abroad may pose a great risk to the household’s economic security due to the exploitive process that migrants must go through.

Reflecting on our group’s research experience

We grew a lot over the 6 days of conducting interviews. The first day, our very first interview was with the ward president. He came out of nowhere during our tour of the village and asked to be interviewed within 15 minutes since he did not have a lot of time. Still unaccustomed to the questionnaire, we hurriedly set up the camera and started our interview. I asked the president question by question as I read them off the script. My voice was shaky, but thankfully it was covered up by Subash’s translation. By the 3rd day, we internalized the questionnaire and was able to communicate more effectively with our respondents, looking them directly into the eye as we said our questions out loud. By the 6th day, the questions we asked our interviewees felt like normal conversations, with strong follow-ups and probes.

When each group presented their research findings at the end of the semester, our group was shocked to find that all other researched communities are facing much more dire challenges than ours. For the other research groups, they interacted with those who lack the most basic necessities of life, which undoubtedly must have been an intense experience conducting interviews everyday. For our group, however, we had a more unique experience since our research site was situated in the valley. The issues here were not as prominent and visible. Water scarcity, while present in our village, was not a dire issue when compared to the other researched communities. The people here still had enough water during the dry season to water their crops and export them to Kathmandu, whereas communities in the mountains must walk 3 hours a day down and up the hills to get water. With access to the Arniko highway, agricultural goods can be transferred easily from the ward to Kathmandu or Tibet. Due to the high economic productivity, the valley has been receiving specific attention from the government, with plans to develop it into a special economic zone for further industrial development. All these combined factors have ensured that the standards of living of our research community to be much higher than the others, while they are only a half-hour drive distance apart.

An interesting dynamic that we noticed within our community was that we did not get a chance to interview that many household members. We were shocked to find that other groups were able to have 10-15 interviews in a row, with lines of people waiting to be interviewed. Perhaps, there was more leisure time in these poorer communities, or because the members wanted their voices to be heard on their life challenges, due to the lack of organizational support. For our village, finding an interviewee was difficult. Life is busier here. Farmers would be working in the fields from morning until late afternoon. Some interviewees were not as interested in answering our questions since so many organizations had come in prior to our group to conduct similar research.

When we come back together next semester to put the final report together, it will be interesting to draw comparisons between our community and the rest. From there, we can identify the determining factors that ensure a community’s economic success in this middle mountain area.

Reflecting back on the Mosaic experience

At Dickinson, the environmental movement and activism existing among students have always been about reducing individual carbon footprints. It has always been about being “sustainable.” It makes you feel good, that as a human being, you have been trying your best to limit your personal destruction on this earth. (Yet, ironically, an average American, living a life of full-convivence, consumes as many resources as 20 people who are from less developed countries.) When discussing climate change and the environment, our major has idealized nature into this magnificent and pure object, destroyed under the hands of human beings, and especially evil corporations. However, this generalization of “humans destroying mother nature” ignores the many challenges and difficulties of people who are at the direct mercy of nature around the world. This is the case for Nepal, where extreme climatic and environmental conditions have been ravaging people’s livelihoods.

I have particularly enjoyed this semester at Dickinson since for the first time, I had the chance to critically examine the interconnections between all aspects of human life and climate change. Climate change will not have just one obvious impact on livelihood, but it will trigger a multitude of responses that will bring about larger socio-economic, political and environmental changes in the future. For example, climate change will impact the agricultural production of farmers, directly decreasing their food and economic security. These effects will prompt farmers to respond in different ways. They may sacrifice other aspects of livelihoods to maintain economic security, such as having their children stay at home to do farm work instead of going to school or having the child-bearing mother overwork on the fields to maintain production level. In the long run, these responses will bring further insecurities to the household. Since this system is so interconnected, there is no silver bullet solution to increase a community’s security against the threats of climate change. Instead, it needs to be a constantly-adapting process that takes into consideration the changing climatic conditions and the available resources and capabilities that can be built upon. In our INTD 250 class, we discussed the steps towards building community resilience to climate change. It first starts with building capacity within the community, providing the people with the basic knowledge and skills that can increase their ability to cope with economic and environmental stresses. Only when all the basic needs of the communities are provided can long-term resilience planning be effective. The research experience in Nepal has also helped me draw a deep connection between international development and climate change. When assessing the resources and capabilities of a community to build resilience, we are basically analyzing the level of development within the community. The presence of financial and social support systems and non-governmental organizations are determinants of both climate resilience and human development standards.

The knowledge that I gained from this experience has been extremely practical and directly connects with my professional interests. As Vietnam is one of the countries that will be most affected by climate change, I have always been interested with the question: “How do we design solutions that can help vulnerable communities adapt and mitigate the threats posed by climate change?” This semester, by researching and answering the question of “what resources and capabilities are available,” I am a step closer towards understanding the subject matter. Vietnam does not share the same geography, climatic threats, or development levels as Nepal. Nonetheless, the human security, community resilience, and systems framework that we applied this semester is still extremely valuable in terms of understanding how to build capacity within a community. In the future, I wish to continue studying international development, while applying a climate change perspective. I hope that this integrated perspective, along with an understanding of the iterative adaptive management, will help me assess both the short-term and long-term needs of communities.

Extra Credit #3: Reflecting on “Sustainability”

Throughout my experience of studying in the U.S., living in Vietnam and traveling through different developing nations, it is always interesting to reflect upon the idea of “sustainability,” in terms of reducing individual carbon footprint, and what it means in each country’s context. Across the United States, there is a movement among the younger generation to reduce our footprints by changing the way that we consume our food, by reducing consumption of beef or buying local food, reducing the amount of trash that enters landfills, increasing recycling rates, and turning off electric appliances to reduce electricity consumption. It is extremely commendable that our generation has become much more environmentally conscious about our consumption decisions. However, the U.S. is no leader on this issue. In fact, all these concepts of reducing consumption levels can be found in any developing country. The difference is that these values are viewed through the lens of “cost-efficiency” rather than “saving the environment.” I remember back in the early 2000s, when Ha Noi still had many power outages issues due to the failure of our national power grid to provide adequate electricity to homes, we had to cut down on energy use as much as possible. Secondly, we didn’t go to grocery stores since Vietnam didn’t have grocery stores back then. Farmers would bring goods straight from their farms outside the city into informal markets on streets and sell them, representing the perfect model of “buy local” that the U.S. advocates for. Our diet mostly consisted of vegetables, pork, and chicken, as they were cheaper to buy than high-quality beef. However, as Vietnam developed over the decades, we have progressed from a lower-income country to a lower-middle income country. People have more money now and they can afford to spend more. As we are able to spend more money, we seem to have forgotten about the values of “conserving energy” or “buy local,” opting for better-looking food products in grocery stores and avoiding any inconvenience in life. Instead of washing clothes by hand, we now buy washing machines. Instead of having to endure the hot summer heats with only fans, we can buy A/C units. Why bike when you can ride a motorbike or drive a car?

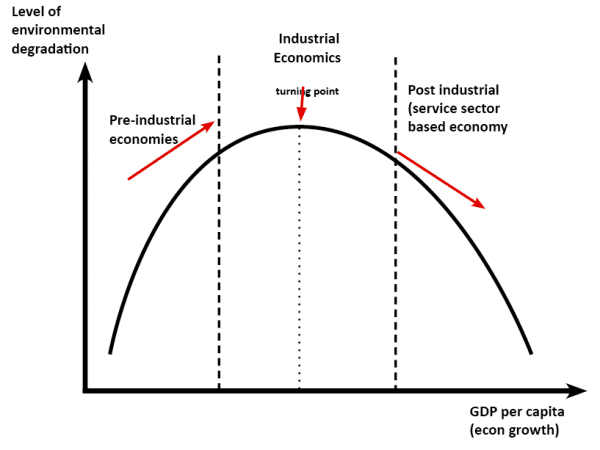

It seems like the idea of sustainability also evolves according to the Environmental Kuznets curve. Citizens of lower-income countries conserve their resources for economic purposes, but as income rises, the value of conserving resources slowly fades away as people become richer and purchase more goods that improve their quality of life. Once the transition to a developed nation has finished and people’s daily life needs are met and life is at highest conveniency, interestingly, this is when people start reflecting again about the idea of “conserving resources,” but this time, through an environmental and sustainability lens.

Extra Credit #2: To ride or not to ride the elephant?

During our stay in Chitwan, we had the chance to bathe and ride with the largest land mammal on earth – the elephant. During our visit to one of the elephant breeding centers, we learned that most commercial elephants are bred and raised in captivity, for the purpose of becoming tourist attractions or aiding forest rangers in patrolling national parks. The treatment condition of these elephants shocked many of the students upon arrival. We learned that to domesticate an elephant, the baby is separated from its mother for a 3 month period, where it is left hungry in order for it to be more obedient to training. The elephants at the center were all chained to poles, unable to move anywhere more than a 3 feet radius. The repeated motion of the elephants trying to break free from the chains was heartbreaking for many of the students during the trip. Due to this poor treatment of elephants in these breeding stations, several students made the decision of not going on the elephant ride the next day. The action of not participating in the elephant ride, for the sake of the elephant, is extremely commemorable. There is nothing wrong with this action. However, I would like to further interpret this decision with my personal point of view on the subject.

Personally, I chose to ride the elephant because I believe the economic benefits that the elephant brings to the community here is more valuable than the well-being of the elephants themselves. Without the national park or elephants as a tourist attraction, there would be no better income-generating activities for the people in the area, especially for the disadvantaged Tharus, who had their rights to use the forest completely stripped away by the Nepali government during the 1990s. By choosing not to ride the elephant, the student has effectively made the decision that “I refuse to exploit this poor animal for my personal gain/ someone else’s gain.” In my opinion, the elephant has been over-idealized due to our rare chances of ever seeing an elephant up-close in real life. Take the ox for comparison. It is exploited by farmers to plow and till land on agricultural fields, which is extremely hard work. If the ox goes in the wrong direction during tillage, it is hit until it returns to a straight line. Once the work is done, it is herded back to its cage, where it remains for the rest of the time until the next workday. Despite this exploitative relationship, the ox is seen as a friend to the farmer, as a pure economic driver, providing manpower and manure for fields. If we apply the same relationship of the farmer to his ox to the mahout and his elephant, we find that they are identical. Through the eyes of the mahouts, the elephant is seen as a pure economic tool, or by the rangers as a vehicle to patrol forests. Inflicting pain upon the animal is not of concern to them, as they serve the greater purpose of generating value for the community. Thus, when making the moral decision of whether or not I want to get on the elephant, despite my personal feelings for the elephant, I chose to take the blind eye. Does this mean I believe that the treatment of elephants shouldn’t be improved? Absolutely not.

Extra Credit #1: Things that shocked me about Nepal

Prior coming to Nepal, with my experience of living in Vietnam, traveling through Mexico, Costa Rica and Panama, I thought that I would have been well-prepared to once again, travel to another developing country. However, I overestimated my ability to adapt to the new culture here. Upon arriving in Nepal, I felt right away that this will be a completely different experience and fell into a culture shock. Everything about Nepal was so different, from its geography to culture and people. Nepal has a unique landscape that could be found nowhere else on earth. During the mornings in the Sunkoshi river resort, the fog fills up the valley. Far away in the distance, you can see the white and rocky Himalayan mountain ranges piercing through the clouds. In terms of history, due to Nepal’s geographic location of being sandwiched between Western China (or formally Tibet) and India, the country has also developed quite a unique culture of its own. Nepal has a beautiful blend of Hinduism and Vajrayana (Tibetan) Buddhism. As we toured all the historical sites in Kathmandu, you can see the presence of both Hindu structures, as well as large Buddhist stupas. While I come from a Buddhist (Mahayana) background in Vietnam, I had limited knowledge of Buddhism, its teachings, and diverse sects until I read more on it in Nepal. Walking around the stupa was a surreal experience. Understanding that the root of Buddhism comes from Hinduism was also surprising, as I have never looked much into the history of neither religions.

Contrasting the peaceful culture and harmonious foggy mornings was Nepal’s traffic. Coming from Vietnam, which already has very chaotic traffic, I would say Nepal is probably twice as dangerous and unpredictable. On our rides along mountain ridges, with roads wide enough to exactly fit two trucks going in opposite directions, leaving just about half a feet of spare space before one can go tumbling down the mountains, trucks speed through each other at speeds over 50km/h. Inside the capital, there seems to be no rule of law regarding transportation. Busses overfill people to the point where there would be 5 people hanging outside the door. At that point, the most effective way of getting out of the bus is to jump out of the windows. This nature of being both so peaceful, yet extremely chaotic at times is how I would sum up my experience in Nepal. Unfortunately, this nature is also applicable to the risks that people here face. Peace exists here only until an extreme event such as an earthquake, major flooding, or landslide happens. In a snap of a finger, under the forces of mother nature, life here can turn into chaos for many people.

The Resilient City Research Assignment

As a response to the prompt:

Select an assignment, discussion, workshop, reading or lecture from one of the Mosaic courses. What did you learn from this activity that is relevant to one of the other Mosaic courses? Or to your major? Or to other interests that you have?

While the assignment on researching resilient cities did not directly connect to our experience in Nepal, I still found it to be very interesting, since I had the chance to understand more about one of the cities in my country – Da Nang. You usually will only know two cities at most in Vietnam – Ha Noi and Ho Chi Minh City, since they are major financial and governmental hubs of the country. Da Nang, up until recent years, has been rapidly developing and gaining the reputation as the third financial and industrial hub in Vietnam. Interestingly, there are certain similarities in terms of climate risks that Da Nang and Nepal share together. To the West of the city, the Annamite mountains block the incoming clouds during the monsoon season. As the elevation slowly decreases into flat plains surrounding the city area, the city suffers major flooding issues during the rainy season that brings heavy damage onto infrastructure and farms. Issues relating to deforestation in the mountain areas has also lead to more intense flash floods during recent decades.

As I have high interest in understanding risks that community face from natural disasters, this assignment, along with the information we learned about Nepal’s environment, helped me understand that the geography of an area has a heavy influence on the climate risks. Just by looking at a map and weather patterns, we can estimate somewhat accurately what climate risks community faces. If there is a mountain next to the community, then there may be issues relating to landslides or floodings. If a community lies in coastal areas, issues such as saltwater intrusion or hurricanes must be considered. If a country is under the influence of monsoon regimes, then there will be high agricultural productivity during rainy season, but decreased productivity in the dry season. Cropping practices may have to be altered to adapt to these changes in the environment.

Forest Governance In Nepal

As a response to the prompt:

How has something you learned or did in the Mosaic increased your curiosity about an issue? Have you or will you act on your increased curiosity? How?

In our recent assignment for Professor’s Beevers class, Marina and I examined the forest governance structure of Nepal. There are many facts that surprised me about the history of forest governance in Nepal and the people’s dependence upon forest resources. These include:

- Nepal went through major changes in its forest governance structure. Before 1951, under the rule of the Ranas and Shahs, the country encouraged conversion of forest to agricultural land to increase its tax base. A major area of forests was also privatized and given to constituents that had close relationships with the family. After 1951, Nepal nationalized all private forests in order to halt the deforestation process. The policy actually backfired when people converted all private forests to agricultural land to avoid the reclamation, which further exacerbated the problem. In order to address this issue, the government decentralized its forest governance system in 1976, and handed forest rights over to local communities. This program successfully halted the deforestation rate in Nepal and is recognized internationally as one of the most successful implementations of community forestry program. As of now, there are over 18,000 Community Forest User Groups in Nepal.

- Nepal is one of the first countries leading the implementation of REDD+ into its forest governance structure. During class, we often mention REDD as a solution to addressing issues relating to deforestation and forest degradation. However, upon further examination, I realized that there are many issues relating to the implementation of REDD+. While REDD+ may help to strengthen forest governance institutions, its aim is to maximize carbon storage within forest ecosystems. This may limit the forest user’s ability to extract forest resources that may be important for their daily livelihoods. While Payment for Environmental Services are in place to compensate for the loss in income-generating activities, this may not be sufficient to cover the losses. Additionally, to maximize carbon storage, fast-growing tree species that do not belong to the natural environment may be prioritized, thus disrupting the forest ecosystems.

As we travel to Nepal, I will try to engage in conversations with villagers and stakeholders about the implementation of community forestry. I want to learn more about the personal opinions of people on this project and understand why it has been such a successful model for forest management. I may also ask them about the implementation of REDD+ to see if the issues raised in these reports are apparent on the field.

INTD 250 Policy Brief: Agricultural Infrastructure Adaptation Through Irrigation

Project Description

This policy brief was written for our Climate Risks and Resilience in Nepal class. The assignment required us to research a selected adaptation or resilience building measure, set of measures, project, program, policy or strategy that has been or could be implemented in Nepal. We chose to research recent efforts made by the Nepalese government to develop and enhance the irrigation infrastructure of the country.

Sector: Agriculture and Rural Development

Adaptation Type: This low regret program addresses current water access issues, while also preparing for potential future challenges and building capacity in this area.

Executive Summary: The Irrigation and Water Resource Management Project aims to more effectively and efficiently utilize and manage water in order to increase quality of life in Nepal, which is heavily dependent on agriculture. In four components, the World Bank and aims to combine improvements to infrastructure with policy reform and education of best management practices to achieve better outcomes in water use and agricultural outputs. While the timeline has doubled from its initial goal of five years, the program has seen great success in increased crop yield for farmers which has led to higher incomes and better quality of life. Additionally, increased water access as a result of this project will allow rural communities to adapt to climate changes in the future.

Actors: The main actors in this program are the World Bank, the Government of Nepal, and the Nepali Department of Irrigation, who designed and run the projects. Also involved are the Department of Agriculture and the Water Users Associations.

Stakeholders: The various stakeholders include the World Bank, the Government of Nepal, the Department of Irrigation, Water Users Associations, farmers, and rural communities. As financiers of the project, the World Bank, the government, and the WUA have a monetary stake in the success of the project. The farmers and rural communities involved in the project are invested as the direct beneficiaries of its success.

Project Details:

Agriculture is a major component of Nepal’s economy, as it contributes to 38% of the country’s GDP (World Bank). However, farmers do not have access to adequate irrigation systems and still depend largely on monsoon rains. According to the World Bank, less than one-fifth of total cultivated land in Nepal receives year-round irrigation. Addressing this problem, The Irrigation and Water Resource Management Project (IWRMP), funded by the World Bank, aims to fund infrastructural development and improve the governing institutions relating to agriculture and irrigation. The project originally started in 2008 and was proposed to end in 2014, but due delays in implementation and additional resources needs, the deadline was extended 2018. The project is divided into four main components:

(A) Irrigation infrastructure development and improvement

(B) Irrigation management transfer reforms

(C) Institutional and policy support and

(D) Integrated crop and water management program (ICWMP)

Enhancing irrigation systems is one of the most effective ways to improve rural livelihoods and enhance climate resilience, especially for the case of Nepal. Cultivated lands will have increased water access, which will enable farmers to enhance their food production. A more productive agricultural system will increase demand for employment. As a result, income for the rural poor will rise. Additionally, as climate change will alter the Indian monsoon, rainfall patterns will become more unpredictable. Farmers will need irrigation systems to ensure a reliable water supply and diversion system.

To ensure that the project is achieving its goals, indicators to measure the progress will include (1) increase in agricultural productivity and cropping intensity; (2) satisfaction from water-user groups; (3) the creation of water user associations and management policies; (4) increase in irrigated areas.

Component A: Irrigation Infrastructure Development and Improvement

This component aims to increase irrigation services from existing systems and develop new systems in three Western Regions, the Mountains, Hills and the Terai. In total, the project plans to improve irrigation water delivery to about 29,000 ha, support groundwater irrigation in 20,500 ha. Specific implementations plans will involve: (1) Improving existing small and medium surface irrigation systems in the proposed project areas; (2) Develop and improve ground water irrigation in the Terai; (3) Support on-demand local irrigation and water supply infrastructures; (4) Investments in non-conventional irrigation technologies, such as drip/sprinkler irrigation, rain-water harvest tanks and treadle pumps. Additionally, the project aims to ensure that all groups will benefit equitably from the project. Disadvantaged groups, such as the landless and dalits, will benefit from special income generating programs and focused investment on non-conventional irrigation technologies.

Component B: Irrigation Management Transfer Reforms

This component aims to reform the current operation and management of irrigation schemes in Nepal by establishing and strengthening Water User’s Associations (WUAs). The WUA will consolidate the governance, management and maintenance of 11 sub-systems of existing five Agency-managed Irrigation systems, including the Koshi West Gravity Scheme, Narayani Irrigation System, Mahakali Irrigation System, Kankai Irrigation System, and Sunsari Morang Irrigation System. These five systems currently covers an area of about 72,500 ha. The establishment of WUA will be complicated as it requires multiple steps to consolidate control of the five systems. These will include: (1) improving the management schemes of the systems to be transferred; (2) conducting field-trainings for WUAs from regional to local levels to increase efficiency; (3) working with the Department of Irrigation to share responsibilities with WUAs; (4) improving the Department of Irrigation’s ability to efficiently invest in the rehabilitation and arrangements of irrigation systems.

Component C: Institutional and Policy Support for Better Water Management

This component aims to build-up relevant institutions through multi-tiered interventions to provide more effective water-management and irrigation-related services. At the national level: (1) A monitoring committee and information center will be established within the Water and Energy Commission to oversee, collect and disseminate data related to water management (2) Policies and regulations related to water management will be amended (3) A system of assessing water availability and allocation to support the operation of water allocation for irrigation systems during periods of drought or floods will be established (4) a platform of communication among different stakeholders, such as civil societies, governments and the media will be created to initiate cooperation of transboundary management of water and energy. In selected river basins, studies will be conducted and legal and technical instruments will be established to address water issues for future hydropower developments and their impact on irrigations. At the level of regional irrigation systems, a census of water users will be conducted and specific regulations to ensure equitable access to water resources will be established.

Component D: Integrated Crop and Water Management

This component aims to incorporate the irrigation infrastructure plans mentioned in Component A and B with downstream agricultural activities to ensure that farmers benefit from the development. The Department of Irrigation (DOI) and WUA will cooperate to (1) promote water-use and management practices (2) introduce agronomic practices to farmers; (3) support agricultural production activities throughout the supply, storage, handling and marketing process.

Resources Needed

The Government of Nepal values this project at US $65 million. The World Bank identified the best source of funding to be a specific investment loan, a type of loan intended to support the development of infrastructure (World Bank Debt Servicing Handbook 9), along with an International Development Association grant. These were viable options because the intended use of funding was clearly laid out and could be completed within five years , although the project timeline has now been extended to ten years. The World Bank granted USD $50 million, the Government of Nepal contributed $10 million, and the WUAs collectively contributed another $5 million. However, the Government of Nepal needs additional funding to complete the River Basin Management Plan, a significant part of the project, whose completion the World Bank will not be involved in.

The Government of Nepal applied to the World Bank for funds for most of the construction projects through National Competitive Bidding. Applying through this pathway (as opposed to International Competitive Bidding) exempted it from competition with other nations. The Nepali government also had to delegate small construction tasks to WUAs, which would require “specialized equipment for MIS, office equipment, vehicles” and other items. Independent parties were also needed to perform research, create a database to track Nepal’s water resources, and provide training (“Project Appraisal” 18). This information and training was needed to help fill in gaps for project teams and government officials previously unfamiliar with the project and associated policies (“Project Appraisal” 19).

Assessment

To promote climate change adaptation, this project should improve the livelihoods of farmers who use these services and their ability to withstand future challenges. The World Bank sets three main criteria to measure the success of the program: service delivery performance, the amount of water collected and the effectiveness of its use, and increases in yield and diversity which bring in greater income for farmers. (“Project Information Document”). Improvements in all of these criteria can help those with access to irrigation to manage current environmental challenges. Better irrigation services provide greater control over how much water crops receive when natural rain is inadequate. Farmers can then grow crops more effectively and make greater profits, and in turn have more economic resources , which boosts their capacity to cope with other challenges.

The project has made progress in all three of the World Bank’s criteria. More than half of the planned irrigation improvements have been completed, and the others are underway. Several training programs have helped farmers to learn new farming practices, which will help them to use the improved irrigation to their greatest advantage. Crop yields have also been successful: The World Bank reports that “The yield of rice, wheat, maize and potato have increased in a range of 39 to 92 percent over the baseline with corresponding increase in cropping intensity from 180 to 242 percent” (“Implementation Status” 2). In the World Bank’s terms, the project made considerable advancement. However, progress has been slower than planned: the deadline has now been extended from 2013 to 2015 (“Implentation Status” 1). Technical and financial shortages have also held back progress on the River Basin Management Plan, which the Government of Nepal will have to complete on its own after the project deadline (“Implementation Status” 2).

The project’s effectiveness also depends on who benefits and for how long. It should benefit those most vulnerable to climate change risks and therefore most in need of adaptation.The inclusion of a “vulnerable group development strategy” ensures that marginalized populations are involved in decision-making processes and enjoy the benefits of the program. Support is also provided to encourage women’s participation in WUAs (“Appraisal” 20). These measures help to ensure that traditionally disadvantaged groups have a voice in the project, and have the opportunity to meet their needs for adaptation. In order to effectively promote adaptation, the project must enable people to meet both current and future environmental challenges. This project is a low regret option because it meets this goal, addressing current needs without creating new environmental problems. Environmental disturbances from construction are expected to be minimal, and actions to mitigate any damage are also built into the plan. The plan also takes future resource use into account. It includes an evaluation of which structural improvements could improve efficiency. An investigation of future prospects for exploiting groundwater will also promote sustainable use of that resource. This increased efficiency should improve farmers’ ability to grow crops when weather patterns they traditionally depend on are disrupted. Overall, the project has been successful in improving the irrigation system in Nepal, effectively increasing farmer’s livelihoods.

Information Sources:

Guidelines: Procurement Under IBRD Loans and IDA Credits. The World Bank, May 2004, http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTPROCUREMENT/Resources/Procurement-Guidelines-November-2003.pdf. Accessed 3 October 2017.

“Implementation Status and Results Report.” The World Bank, 1 Aug. 2017,

http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/274841504214379427/pdf/Disclosable-Version-of-the-ISR-Implementation-Status-and-Results-Report-ISR-NP-Irrigation-Water-Resources-Management-Project-P099296-Sequence-No.pdf. Accessed 3 October, 2017.

“Integrated water resources management in Nepal: key stakeholders’ perceptions and lessons learned.” Taylor and Francis Online, ” http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07900627.2015.1020999. Accessed 3 October, 2017.

“Nepal: Irrigation and Water Resource Management.” The World Bank, 11 Apr. 2014, http://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2014/04/11/nepal-irrigation-and-water-resource-management. Accessed 2 October, 2017.

“NP Irrigation and Water Resources Management Project.” The World Bank, http://projects.worldbank.org/P099296/irrigation-water-resources-management-project?lang=en. Accessed 1 October, 2017.

“Project Appraisal Document.” The World Bank, 1 Aug. 2017, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/500641468323052350/pdf/41409optmzd0NP.pdf. Accessed 2 October, 2017.

““Project Information Document (PID): Concept Stage.” The World Bank, 26 Sept. 2007, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/263431468123880942/pdf/Project0Inform1cument1Concept0Stage.pdf. Accessed 3 October 2017.

“Welcome to Irrigation Water Resource Management Project.” Department of Irrigation, http://doi.gov.np/iwrmp/index.php/1-welcome-to-irrigation. Accessed 3 October, 2017.

World Bank Debt Servicing Handbook. The World Bank, June 2009, http://siteresources.worldbank.org/PROJECTS/Resources/40940-1250176637898/Engl.pdf. Accessed 4 October 2017.